Des Lewis’s classical music reviews HERE

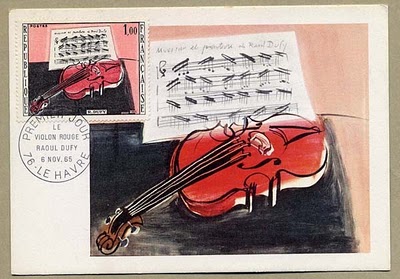

Raoul Dufy:

Filed under Uncategorized

Berghaus had his own armchair in the alcove. Mr and Mrs Swindon had become so accustomed to his presence in the parlour — following a dozen exhausted rent-books — they almost forgot he was a lodger. His face, after all, owned a generous brow teased by the tousled ends of his hair. A real gentleman, they conjectured, despite his intermittent designer stubble. There were even dimples which seemed to sink to the bone in his most lightsome moments.

Berghaus did not need to say anything to radiate his feelings, sad or otherwise. Mr and Mrs Swindon treated him as their own son, or at least a son-in-law. He possessed pride of place under the standard lamp, with an open Dickens on his lap. Listening to music with a pair of heavy-duty headphones long before bluetooth was invented, and he tried to ignore the flickering images on the TV screen that the bleary-eyed Swindons found time to watch so avidly.

He had tried to interest the old couple in one of his passions: Grand Opera and, despite being set in their ways, they had at first sat patiently, closely attending to his views on this rarified subject … until they realised it was all about raucous noises that only riled rats.

“I prefer the stylised beauty of Mozart to the more overt gothicism of Wagner or even Puccini.”

The couple nodded in unison, whilst pretending to keep close examination of his lips and at least one eye upon the silent screen and its teletext subtitles for the deaf.

“And I’ve always thought that there was more to Bellini than Norma.”

Again the couple made a studied aknowledgement while humouring each other with regard to these things that went over their head.

One day, the Swindons’ daughter Petula returned home, having had a hard time with someone who was fast becoming the best candidate for her first ex-husband. The Swindons, of course, bustled round her, tending to their darling’s needs, making oodles of heart-warming tea, clucking sympathies twenty-four to the dozen in their endearingly incomprehensible way, and maligning that brute of a man she had been enticed into marrying. They also flicked glances at Berghaus so that he, too. would try to bolster their daughter’s spirits because, despite being a lodger, he had all the duties of a family friend. So, Berghaus smiled knowingly from between the noisy ear-vice of his head-phones.

He had met Petula only once before, during her brief Christmas visit with the now soon-to-be ex-husband six years before, when she had been a delight to behold with many split skirts: one for each of her moods. The husband had been all mouth and trousers, true, but was very generous with his money, giving the Swindons large Christmas presents and Petula costly jewellery. The marital problems that had now overtaken them, Berghaus guessed, were ones concerned with the source of such riches having dried up. The husband had been summarily dismissed from his employment for breaking the Data Protection Act — was what Berghaus gathered. He didn’t like the look of the barely noticeable bruise on Petula’s upper left leg. It seemed to portend more than what was on show.

A day or so later, Berghaus found Petula sitting in the kitchen darning one of Mr Swindon’s socks over a wooden mushroom. The old couple had gone to what they delightfully called their Doorpost Club which happened every Wednesday afternoon: a tea dance affair by all accounts.

“I’m sorry to hear that things have not been going too well, Petula.” Berghaus shuffled, embarrassed at finding himself alone with her.

“Thank you.” She looked prettier than when she had arrived in a flurry of tears and luggage. Calmer, too. More stoic and forebearing.

“Shall I make us a pot of tea?” he asked, as he inadvertently discovered a loose tooth with his tongue.

“I don’t like to drink tea any more.” She had evidently not had the heart to tell her Mum and Dad this fact, since a strong hot cup of the stuff was the first thing that had met her when arriving upon the parental doorstep. Berghaus suddenly saw a face at the kitchen window: whiskery and scowling. That was all he remembered. The moment had been very short.

Scuffing his feet by the sink and realising that Petula could not have seen the face —her back being turned to the window — Berghaus was naturally perturbed by the incident. There had been an uncanniness about it but one which he found difficult to define: marginally this side of normal: the safe side. He hastily poured himself a cold drink and left her weaving the midget loom she had already erected over the head of the wooden mushroom.

When Mr and Mrs Swindon returned from the “Doorpost Club”, they were blushing with elderly excitement. Grunts and grimaces, as they told of this and that: Marjorie had broken her ankle in the ice last week; Claudette was seeing a little too much of Mr Smith-Bobrowski; Charlie Musker had died of something strange; Dame Florence sent her kind regards to Petula and would like to see her at the club some time (men were getting younger and younger all the time the Dame had said); the brass band had got lost in the snow, so they’d danced to records (not quite so satisfactory, since the dance floor’s vibrations were more attuned to live music); and, by the way, Charlie Musker had left a lot of money to someone in Redditch; what’s more, Lady Dora Slight was coming round tonight to see Petula.

The brass band roaming the icy steppes of Hertfordhshire seemed an amusing concept to Berghaus, whilst Petula seemed irritable at the last piece of news regarding Lady Dora. Berghaus was then abruptly granted another glimpse of the whiskery face, followed by loud fumblings at the back door. Mr and Mrs Swindon didn’t notice, but Petula visibly blanched. There were no vocal accompaniments from the budding intruder and the door eventually came to rest on its hinges. The storm was over … at least for a while.

Berghaus looked as sympathetically as possible at Petula. She returned his glances unalloyed. Having been told to grin and bear misfortunes all her life by suffering parents, she was now reaping the reward of such lessons. She even began to smile when Mr Swindon cracked a joke about her darning, and he wielded her wooden mushroom, pretending to be a conductor of one of those opera orchestras so dear to their lodger.

Berghaus decided to leave them to it and enter the security of his sound-proof ear-phones. Verdi was already on the turntable, so there was little fuss and bother. Eventually, a while later, he re-emerged from the armchair’s sanctuary, only to hear the voice of a strange woman coming from the kitchen-diner. It sounded shrill and strident as if she were rehearsing a recitative from a Rossini opera. Must be Lady Dora.

Supper was a memorable affair. Lady Dora had been invited to share the meal, together with a gentleman companion with whom she had originally arrived. He was evidently her latest beau, a portly individual with scrupulous table manners. Although his conversation lacked point, he certainly made up for this with the number of words he used to fill in the otherwise embarrassing silences. Lady Dora and Berghaus were the only ones who made fitful attempts at repartee, whilst Petula and her parents found sufficient pleasure in merely eating. Petula in particular appeared unwilling to speak even when spoken to. Berghaus kept glancing at the window in case he missed another glimpse of the chap with side chops. It was dark outside now, so it was difficult to imagine the golly-black shape that would probably indicate the chap’s return.

Nevertheless, eventually, there it was, a shadow sucker upon the glass.

Berghaus stood up and pointed. Petula screamed. Lady Dora and her companion were left with silent open mouths. Mr and Mrs Swindon turned towards where Berghaus pointed … but, too late, since the shape had disappeared. But the door’s hideous rattling resumed from late afternoon. This time, Berghaus held out no hope for the hinges as he watched them buckle. Again, however, the din subsided and there was noticeable relief upon all the faces inside the kitchen, despite the fact that some of them failed to realise what it was they were supposed to be relieved about.

Lady Dora scuttled between the two elderly Swindons, calming them, laying her hands upon the tops of their heads and purring like a big cat. Her gentleman companion stood behind Petula, his hands sliding down her shoulders towards the breasts, clucking with sympathy. Berghaus was the only one physically disconnected from at least one other person present. He was reminded of a sextet piece from Rossini’s La Cenerentola. Or was it Bellini’s Norma? He had uncharacteristically forgotten.

He took up the discarded wooden mushroom still bearing the half-finished sock and waved it about like a magic wand. He was slightly perturbed that the window now framed a full moon, more bright than he’d ever recalled ,with markings quite different from those he recalled from his childhood astronomy book. At least, it must have stopped snowing.

In the distance he heard the sound of a brass band playing carols … as the door imperceptibly began to revive. Berghaus yearned for the refuge of his trusty ear-phones. But nightmares woken into are more dreadful than those waken from.

Petula walked to the back door and opened it. She kissed a wolfish thing standing there with blue teeth, and waving its tail about — hugely howling, as if it wanted to scorch the lining off its throat. Or to strip its skull-lining as if it were old wall-paper revealing ancient scored atonalities beneath.

Mr and Mrs Swindon, together with Lady Dora and her limping consort, fled past the now dissolving shape of shagginess, as if they believed staying in the cosy house was more horrific than risking the night outside. Petula turned towards Berghaus with a smile on her lips, her face webbed over with a darning of darkness and her toadstool tongue poking for a second kiss. Berghaus held one long note of baying bestiality, as if performing a pre-scored solo at the dead stereophonic centre of his own head-space of sound. But whose voice was it?

Filed under Uncategorized

Last night, after listening for a solid week to their new powerful ‘complete string quartet’ Zemlinsky CD, I attended a concert by the great Brodsky Quartet at the Mercury Theatre, Colchester, as they vivaciously stood around the cellist, in front of effectively severe acoustic panels…. & Zemlinsky, through his transcendent fourth quartet, came alive and hovered above their heads. Berg eat your heart out.

More from me later after this Wow! effect has worn off.

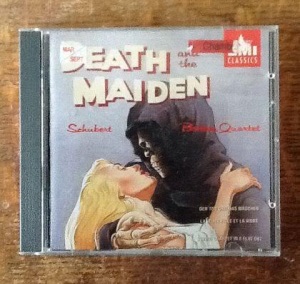

They also memorably performed with internal commands in its last movement, the Death and the Maiden quartet by Schubert. I do, however, prefer his D804 and D887 quartets.

And an early op 18 Beethoven. Vivacious in a different way.

Filed under Uncategorized

I have just received my purchased copy of ORFEO by Richard Powers

Atlantic Books 2014

This sounds as if it should serendipitously resonate with my very recent reading of ‘Doctor Faustus’ by Thomas Mann and my editorship-publication in 2012 of a multi-authored anthology book of Classical Music Horror Stories…

Filed under Uncategorized

You must be logged in to post a comment.